Are the best schools the best?

For decades, for reasons not necessary to elaborate here, there has been an attempt to make colleges more "rigorous," which resulted in an increased emphasis on credentials and research. This is certainly a good thing, as better educated, better trained, better engaged (with one's discipline) professors are likely to result in better college teachers and better college teaching. Unfortunately, instead of investigating and emphasizing how doctoral education, teaching training, and professional development would better college teaching, colleges used the emphasis on rigor as a competitive mechanism to create perceptions of excellence and prestige.

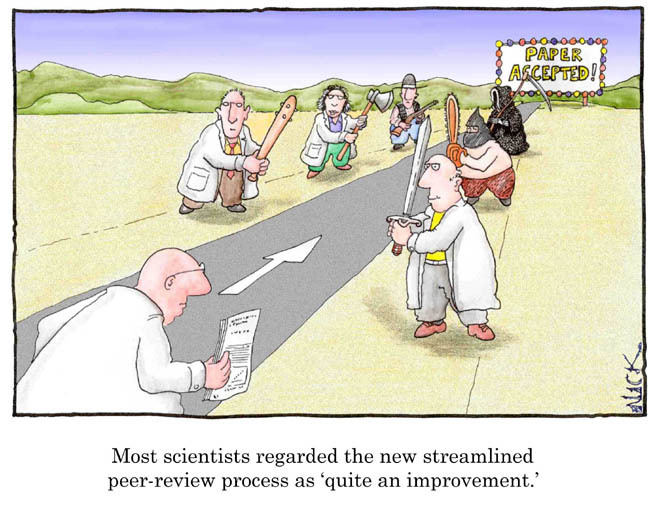

For decades, for reasons not necessary to elaborate here, there has been an attempt to make colleges more "rigorous," which resulted in an increased emphasis on credentials and research. This is certainly a good thing, as better educated, better trained, better engaged (with one's discipline) professors are likely to result in better college teachers and better college teaching. Unfortunately, instead of investigating and emphasizing how doctoral education, teaching training, and professional development would better college teaching, colleges used the emphasis on rigor as a competitive mechanism to create perceptions of excellence and prestige.One easy way to measure that was to increase the number of faculty with doctorates, and this remains a measure of quality of an institution in the sense that it separates the bad schools from the not bad schools. But percentage with doctorates in field no longer differentiates good schools, as most good colleges have long had virtually all of their full-time faculty with doctorates. This degree is now necessary but not sufficient, as it is a sine quo non ticket for admission rather than a symbol of quality. But rather than attempt to measure contributions to learning, which is hard to do well, the easiest, most measurable way to attain the perception of quality became the number and quality of publications (and its offshoot, quality of graduate schools). Schools could measure and compete on this dimension, and the desire for prestige became the chase for research publications. This measure of quality has become very sophisticated, with peer-reviewed journals (PRJs) the gold-standard, replete with different tiers of journal quality, rules for quality of author position (meaning first author more valued than second author, etc.), currency of topic, number of publications, level of quantitative rigor, amount of citations generated, etc., the discriminators of professor and institution quality.* In some disciplines, grants are an important currency, and in some cases, innovative outputs such as patents matter, each with their own hierarchies of value.

Thus were born research schools, which tend to generate more income from grants, endowments, the ability to charge higher tuitions, donations, etc., which in turn allow these schools to offer higher salaries. In offering these higher salaries, these schools then have the ability to attract those faculty attracted to salary and prestige. To perpetuate and increase prestige and resources, the faculty with the greatest potential for "productivity" are hired, and those most "productive" rewarded (tenure, resources, etc.).

Faculty at research schools quickly learn that teaching is low on the extrinsic reward totem pole (and intrinsically often those motivated to be prolific researchers are not also motivated to be excellent teachers), so the motivation to teach well is naturally diminished. Couple this with the institution's desire to support research over teaching (reduced teaching loads, large lecture classes, use of teaching assistants, research release time, use of adjuncts, etc.), and it is small wonder that the prestigious research schools typically pay little more than lip service to quality teaching.

In fairness, some of the most prestigious universities are returning to basics in an attempt to reinvigorate long-lost ideals of quality teaching in devoting resources to teaching training and rewards, whether due to changing accreditation standards, assurance of learning demands, or the conscientious reformation of mission. But the moral typically remains that if you are at a "prestigious" school (and probably paying a very high tuition for the privilege), you are highly likely to graduate with a more prestigious degree but have received an inferior education.

* In some instances, the creation of perceptions of quality by academic scholarship may be circumvented by the success of athletic teams, i.e., the Notre Dame model, which ironically may then lead to the generation of superior scholarship via the increased direct (tickets, media, merchandise, etc.) and indirect (donations, endowments, alumni, tuitions, etc.) income generated by the successful athletic program, which allows the school to buy higher quality (more productive) faculty. In essence, a strong athletic team may (but not necessarily- see UNLV basketball) lead to a strong academic reputation.

Labels: best colleges, College teaching, research schools

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home